주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Dark Matter Axion Group

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Center for Relativistic Laser Science

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Dark Matter Axion Group

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Center for Relativistic Laser Science

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

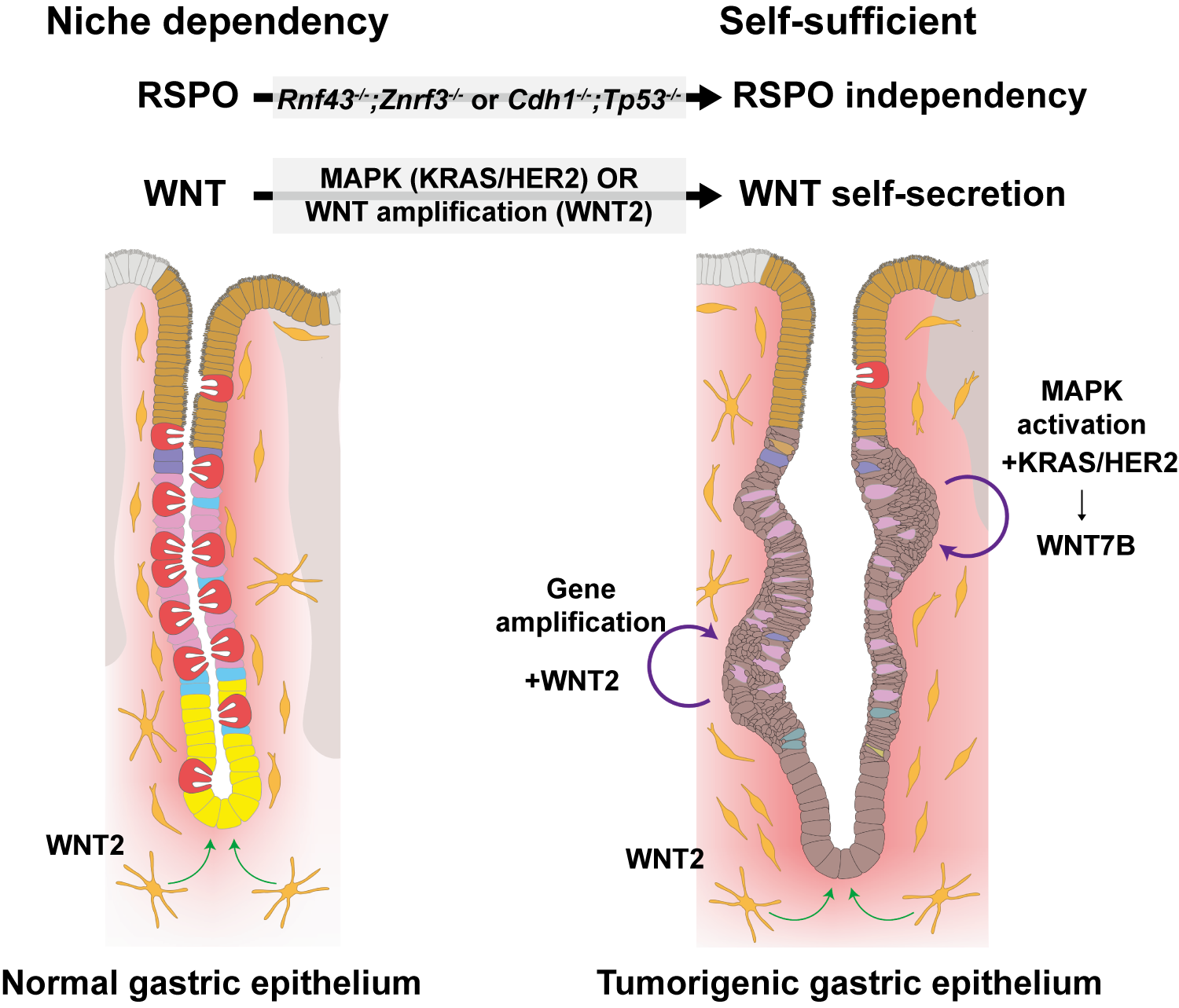

Researchers Discover How Stomach Cancer Learns to Grow on Its Own- Study reveals a mechanism by which early gastric cancer cells become independent of their microenvironment, opening new avenues for targeted therapy - Gastric (stomach) cancer remains one of the most common and deadly cancers in East Asia, including Korea. Yet despite its high prevalence, it has received far less molecular attention than colorectal cancer, which is more common in Western countries. As a result, many of today’s models of gastric cancer biology are still based on assumptions borrowed from colorectal cancer research — often with limited success when applied to patients. One of the biggest unanswered questions has concerned the very first steps of gastric cancer development: how do early cancer cells survive and grow when they should not? Under normal conditions, cells lining the stomach cannot grow independently. They rely on constant signals from their surrounding tissue — known as the microenvironment — to tell them when to divide, when to rest, and when to die. Losing this dependence is one of the defining features of cancer. But in gastric cancer, researchers have long struggled to explain how this transition occurs. This problem has been tackled by a joint international research team led by Dr. LEE Ji-Hyun, Dr. KOO Bon-Kyoung, and Dr. LEE Heetak at the Center for Genome Engineering within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), in partnership with the laboratories of Prof. CHEONG Jae-Ho and Prof. KIM Hyunki (Yonsei University College of Medicine) and Prof. Daniel E. STANGE (TU Dresden / University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus). The team has identified a previously unknown mechanism that allows early gastric cancer cells to become self-sufficient. The findings provide a new framework for understanding how stomach cancer begins — and point to potential new targets for treatment. The inner lining of the stomach is one of the most dynamic tissues in the human body. It is continuously exposed to acid, food, and mechanical stress, and must constantly regenerate. To maintain this balance, stomach cells depend on tightly regulated molecular signals that control growth and repair. One of the most important of these signals is called WNT signaling. In healthy tissue, WNT molecules are supplied by neighboring “niche” cells that act like caretakers, allowing stomach cells to survive and divide only when appropriate. Without these external signals, gastric epithelial cells simply cannot grow. In colorectal cancer, this system breaks down in a well-known way. Mutations in genes such as APC or CTNNB1 permanently activate the WNT pathway, allowing cancer cells to grow uncontrollably without outside help. Surprisingly, these classic mutations are rare in gastric cancer, leaving researchers puzzled for decades about how WNT signaling becomes activated in the stomach. The new study shows that gastric cancer cells solve this problem in a very different way. Instead of waiting for WNT signals from their environment, early gastric cancer cells begin producing the signals themselves. In effect, they stop listening — and start talking. The researchers discovered that activation of another major pathway, known as MAPK signaling, triggers this switch. MAPK is a signaling system that normally helps cells respond to growth cues and stress. In gastric cancer, it is frequently activated by mutations in genes such as KRAS or HER2, which together are found in roughly one-third of patients. When MAPK signaling is turned on, the cancer cells begin producing a specific WNT molecule called WNT7B. By secreting this molecule, the cells create a self-sustaining loop: they supply their own growth signal, activate WNT signaling internally, and continue to proliferate even in the absence of normal tissue support. “This is a fundamental change in how these cells behave,” explained Dr. LEE Ji-Hyun. “They effectively become independent of their environment at a very early stage.” The study reveals an unexpected functional link between the MAPK and WNT pathways — two of the most important signaling systems in cancer biology — and shows how their interaction drives early tumor growth in the stomach. Crucially, the team demonstrated that this mechanism is not an artifact of laboratory models. The findings were first identified using genetically engineered mouse models, but were then validated in gastric cancer patient-derived organoids — three-dimensional mini-tumors grown directly from human cancer tissue. These organoids closely mimic the structure and behavior of real tumors, making them a powerful bridge between animal studies and human disease. To build this resource, the researchers conducted long-term domestic and international collaborations with Yonsei University College of Medicine and University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus Dresden, collecting gastric cancer samples from diverse patient groups. The consistency of the results across species and platforms confirms that the newly identified mechanism is directly relevant to human gastric cancer. Beyond answering a long-standing biological question, the findings open new therapeutic possibilities. Gastric cancers by this MAPK-driven WNT self-activation currently lack effective targeted treatments. By identifying how these tumors sustain their own growth, the study highlights vulnerabilities that could be exploited to block tumor initiation at its earliest stages — before the disease becomes advanced or resistant. Building on this work, the research team is now actively exploring strategies to selectively disrupt this signaling program while sparing normal gastric tissue. More broadly, the study reflects a growing shift in biomedical research toward human-relevant experimental systems. As the limitations of animal-only models become increasingly clear, regulatory agencies such as the U.S. FDA have emphasized the importance of patient-derived platforms, including organoids. By combining mechanistic insights from mouse genetics with direct validation in human tumors, this work exemplifies a modern translational research pipeline aligned with global research priorities. The study was published online as an Early Access article in Molecular Cancer (Impact Factor 33.9). 그림 설명

Notes for editors

- References

- Media Contact

- About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) |

| before |

|---|

- Content Manager

- Public Relations Team : Yim Ji Yeob 042-878-8173

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20