Discovering new knowledge in daily

life through interdisciplinary research Director Steve Granick, Center for Soft and Living Matter

The IBS Center for Soft and Living Matter is at Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST), located north of the Taehwa River crossing Ulsan. The director of this Center is Steve Granick, one of the world’s greatest scholars in polymer physics

and chemistry. We interviewed the master

of convergence, who emphasizes the

value of collaboration among people from

different backgrounds to make exciting new

discoveries.

“There are many people who deserve this. I

was one of the lucky people. It is especially

good for people who work with me because

it will open new possibilities for them. It also

becomes the responsibility for us here at IBS to

do even better work here in Korea,” said Steve

Granick, Director of the IBS Center for Soft

and Living Matter, telling us he received many

calls congratulating him on his election to NAS

in late April. Director Granick is a distinguished

professor at UNIST and founded the IBS

Center for Soft and Living Matter in 2014.

We met him at the UNIST campus where the

Center is located to hear about the Center’s

recent achievements and future plans.

Steve Granick worked with John Ferry, the

greatest scholar in polymer physics and

chemistry at the time, during his doctoral

program, and with Pierre-Gilles de Gennes

(the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991) as a

postdoctoral researcher. Granick had been a

professor at the University of Illinois for 30

years. Interestingly enough, he received both the

Polymer Physics Prize awarded by the American

Physical Society and the National Award in

Colloid and Surface Chemistry awarded by the

American Chemical Society. He is regarded as

a world-class scholar in polymer physics and

chemistry.

Physicist-chemist emphasizing

convergence

Talking about the awards, Director Granick

said, “It is not common to get these awards, one

in physics and one in chemistry. But that is the

interdisciplinary work that we specialize in. We

are curious about the whole world. If you open

your eyes, you don’t see a separation between

different disciplines, so it makes sense to work

in different fields.” He studied sociology as an

undergraduate, but changed his research field to

chemistry as he thought that the way to do science

is rather defined. When he became a professor,

he started working in many different fields. He

believes that he would have had to say no to too

many problems that could be interesting if he had

wanted to just work on one thing.

This philosophy is also reflected in the direction

of his Center, for it conducts research on not a

single particular field but various fields related

to our daily lives. In fact, soft matter is about

the physics of daily life, about discovering the

underlying simplicities in daily life, complex

though it is.

When Director Granick was asked to explain

his research field, he said, “To me it is whatever

is interesting. If something is interesting, we should study it.” He added, “It occurred to

me that in the 21st century we should study

not only inanimate matter (soft matter such as

polymer, water, etc.) but also life. I do not want to

compete with biologists, but still, we should try

to make a bridge between natural science and

biological science.” For instance, juice is a liquid

with floating matter. In order to study how to

thoroughly mix the solute and solvent of the

juice, polymer science and colloid science should

be related. “It is daily life,” Director Granick

added. “We want to understand the world we

see around us. There are so many things in this

world that no one understands very well. We

want to contribute to the world by attempting

to improve this understanding. We don’t have a

rigid program; rather we are following discovery

type of research. But we know from experience

that when scientists understand daily life better,

there are technologies that can be improved as a

consequence.”

Director Granick has placed a special emphasis

on research that transcends the scope of a

single discipline. His Center also takes a highly

interdisciplinary approach. “To understand

it completely, we have to use all disciplines,”

he said. He tries to avoid questions that many

others have already worked on. He believes that

it is important to choose unexplored problems

where his research can make a difference. In

other words, he does interdisciplinary research

because he can find new things and thus

improve the world.

The Center regards recruitment of talented

people as the most important necessity for

interdisciplinary research. Director Granick

said he works very hard to find senior scientists

and group leaders who are smarter than he

and also have different backgrounds and the

personality to talk to each other. He believes

that when smart people who know different

things have debates and explain their ideas, they

will formulate new and interesting questions.

“I think the best recipe to be creative is don’t

tell people what to do. Just find good people

and let them figure out what they should do.

This is what very special about IBS.” He also

said, “Korea invests in long-term questions,

not just short-term, engineering solutions.

And the country is very wise in having such a

big ambition these days especially when other

countries are becoming less ambitious.”

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS)

is one of the most authoritative and

prestigious academic organizations in

the world. Many Nobel Prize laureates,

including Einstein and Watson and

Crick – who discovered the structure

of DNA – were NAS members. Election

to the organization is akin to gaining

international credibility for one’s academic

achievements and is considered one of

the highest honors a scientist can receive.

Molecules in a cell have intelligence?

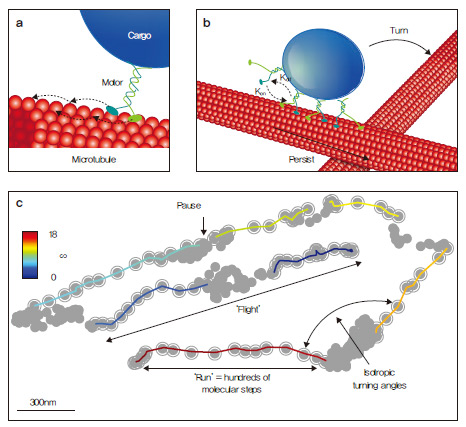

a. Trajectories of endosomes in

live cells. Cargo is transported

along microtubules dragged by

molecular motors.

b. Microtubules extend in

multiple directions and cross

paths to form networks. Multiple

motors can change transport

directionality by binding

simultaneously to work as a

team.

c. A representative trajectory

with runs, turns and flights.

© Kejia Chen et al. / Nature

Materials

The Center recently released an interesting

finding on the movement of matter in cells. To

be specific, it found a movement pattern called

“Lévy walk,” through which molecular matter,

which lacks intelligence, efficiently searches

and moves toward a destination as if having

intelligence. This finding was published on

Nature Materials on March 30th.

Scientists have long studied how a cell moves

matter to a target destination. This is like

knowing how a mail carrier delivers mail to a

destination. Research in the past concentrated

on how the delivery vehicle operated, while

little research was conducted to understand the

road map through which the mail reached the

desired destination. The Center grew interested

in the delicate mechanism by which matter in a cell could be delivered to its final destination.

The Lévy walk is a term coined after the

French mathematician Paul Lévy. When finding

food, animals such as honey bees, jelly fish,

sharks, or human beings move within a region

changing directions irregularly and frequently

but sometimes going a long distance. Such

random behavior patterns or phenomena are

called Lévy walk. This research is significant in

that the Lévy walk is found in movements of

molecular matter that does not have intelligence

or memory while the premise of the pattern

revealed thus far was the intelligence of animals.

The Center paid attention to the movements

of molecular motors that transport matter in a

cell. Molecular motors are proteins that control

the various operations (cell division, intracellular

transport, cell movement, etc.) required to maintain

the function of a cell. They deliver matter like

ions, sugar, and amino acids to a particular

place through microtubules stretched like a

road network within a cell. Microtubules, a

kind of protein fiber in the shape of a hollow

cylinder, keep the cytoskeleton consistent and

are involved in cell migration.

Researchers at the Center observed the

movements of the “cargo,” endosomes in a

living cell, dragged by molecular motors and

found that the motors showed a pattern in

which they would randomly and cautiously look

around but occasionally move a long distance.

It was found that this Lévy walk was caused by

a tendency in the direction of movement. In

other words, the direction frequently changes

when searching and moving within a close area

while there is a tendency to keep moving toward

a goal if the goal is in a remote place.

Talking about the functional advantages of the

Lévy walk, Director Granick said, “I was surprised

and charmed to learn that molecular motors

don’t have to run on gasoline or electricity.”

The Lévy walk is a far more efficient way for

cells to find places they need to go as it allows

the quick and random searching until cells

find the right place than could be done by the

slower Brownian motion. He explains how the

Lévy walk is different from Brownian motion:

Brownian motion is like when you put some

milk very carefully into coffee and don’t stir it.

You will see the milk mix very slowly. If we stir,

it mixes much faster. That is the Lévy walk and

it is one way that nature has discovered to stir

the contents of our cells.

The “Lévy walk” research was supported by the

Department of Energy (DOE) and it is also the

result of collaborative work with researchers of

the University of Illinois. The research began in

an interesting way. Director Granick said, “I did

not work on cells until I met an excellent Illinois

university student, Bo Wang (2nd author) who is

now a Stanford University professor with his

own laboratory. To find a way to interest him so

he would work with me, we began looking inside

living cells. That led to the paper.” He said

the paper simply shows how interdisciplinary

research works. “Bo Wang worked very closely

with the first author, who is expert in statistics

and mathematical analysis modeling, to make

the final paper. It was imperative to have them work together. One discipline could not have

done it.”

Fresh stimulation to the scientific

community in Korea

Researchers from around the

world are working at the Center

for Soft and Living Matter.

Director Granick hopes that

talented people with various backgrounds will join the Center

The Center expects to continue interdisciplinary

research as scientists with various backgrounds

continue joining. According to Director

Granick, Professor Amblard from a renowned

lab in Paris, theoretical physicist Dr. Tlusty

from the Princeton Institute of Advanced

Study in the U.S., Dr. Grzybowski from

Northwestern University in the U.S., and

Professor Yoonkyoung Cho of UNIST have

newly joined the Center. Professor Amblard

majored in mathematics, biology, and physics;

Dr. Grzybowski majored in mathematics,

physics, chemistry, and biology; and Professor

Cho is a nanomedicine expert who has 10 years

of experience of DNA chip R&D at Samsung

Advanced Institute of Technology.

Director Granick said, “These smart people will

decide which direction our Center’s research

will go in the future,” and stressed, “It is not I

but we, our scientists who decide the direction.”

His Center will also work on biologically

inspired research. For example, blinking our

eyes is a way to lubricate our eyes. Water seems

so simple, but we depend on it in a way we do

not fully understand.

His Center is building state-of-the-art research

facilities such as imaging facilities and NMR.

Director Granick emphasizes that it is important

to use the technology of the 21st century and

bring it to Korea to advance research. He said

he used a number of research devices to see

everything that happens inside cells. Talking

about research methods using many research

devices, he said it took two years to find

florescent molecules that cells like to eat.

Director Granick said, “I love IBS’s ambition

to be different from what others are doing,

UNIST’s full support, IBS researchers’ creativity

and hard work, great research facilities, and

openness to welcome Westerners who still

do not speak Korean well.” He hopes that

his Center will promote more international

collaboration with Japan, India, and China as

well as U.S. and Europe. He has also previously

worked as a professor in China and France.

Talking about the ultimate goal of the Center,

Director Granick said, “No one person’s

achievements last very long. The only longevity

is students. Though one of my mentors won

the Nobel prize, I have noticed that people

forgot his name some time afterward. But he

continues to have influence through me and

his other students. I aspire to do so through my

researchers here at this Center.” He added, “If

we are successful, we will influence the agenda

of other scientists. Korean science shows to the

world that here is an important problem and we

need to work on it to improve the world.”

|

s_thumb.jpg

s_thumb.jpg