주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

| Title | The Life and Discoveries of a Nobel Prize Winner | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Department of Communications | Registration Date | 2016-10-31 | Hits | 3445 |

| att. |

thumb.jpg

thumb.jpg

|

||||

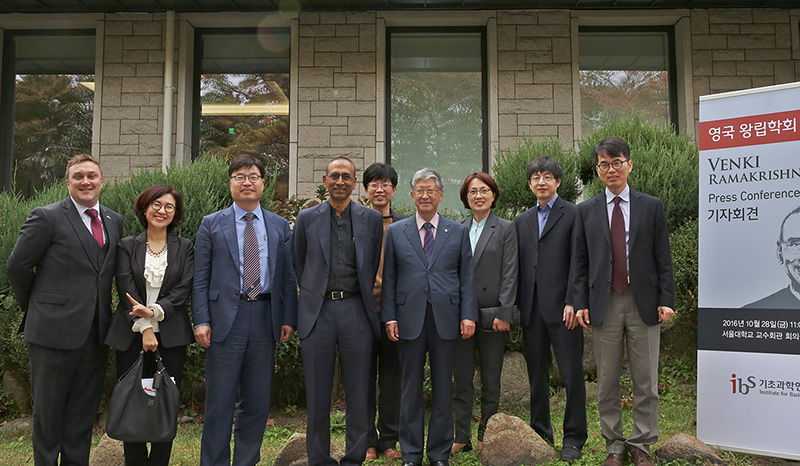

The Life and Discoveries of a Nobel Prize Winner- Venki Ramakrishnan, President of the Royal Society, "Science is not only about great discoveries. The first and most important attitude is to have a really genuine curiosity about your problems." -

"What do Keats, Kafka, Orwell, Mozart, Schubert and Chopin all share in common? They are all famous artists, but another thing they share is the fact that they all died very young of infectious diseases. Now, we have pills and we tend to think that infections are not a problem anymore, but the reality is that lots of people die of infections." This is how 2009 Nobel Prize winner Sir Venki Ramakrishnan (Laboratory of Molecular Biology, LMB, UK), President of the Royal Society introduced the issue with antibiotics resistance at his talk in Seoul on October 28, 2016. To celebrate its incoming fifth anniversary, IBS invited Prof. Ramakrishnan to present the science behind antibiotics resistance, to describe the latest research in the use cryo-electron microscopy to study the ribosome, and to share memorable experiences of his career. The first antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered by Alexander Fleming during the Second World War, when more soldiers died from infections than by bullets. Penicillin improved the situation dramatically, but when Fleming received the Nobel Prize in 1945, he warned that bacteria would become resistant to it. And he was right. Indeed, since then, resistance to penicillin increased sharply, so much so that now almost all Staphylococcus aureus bacteria are resistant to it. Over the years, a lot of bacteria strains became resistant to more and more drugs, and according to the 2014 Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, around 700,000 people die of drug-resistant infections every year. This figure is expected to soar to 10 million by 2050.

How do antibiotics work?Prof. Ramakrishnan explained that while penicillin targets the cell wall of the bacteria, several types of antibiotics work by preventing bacteria from producing their proteins. Proteins are produced from information present on DNA, which is transcribed into mRNA and translated into proteins. Cellular organelles called ribosomes help during the translation process and are considered 'the cell's protein factory'. Unraveling the 3D high resolution structure of the ribosome led Prof. Ramakrishnan to jointly win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009. The detail structure of the ribosome might help to clarify some unsolved questions regarding the beginning of life on Earth. For example, one kind of "chicken or egg dilemma" is the following: If the ribosome makes proteins, but it is made of proteins, what made the ribosome? The ribosome structure has showed that the active site for peptide-bond formation has a core made of RNA only, so it is possible that the ribosome was initially an RNA machine without proteins, and only later proteins were added to it. Other scientific advances that became possible with the 3D structure of the ribosome regard mechanisms of action of antibiotics that target the bacterial ribosome. The antibiotics that we use to cure infections act on sites where bacterial ribosomes are different from human ribosome. "Antibiotics target the key weak points of the machine that can be blocked," explains the professor. So how do bacteria become resistant to antibiotics?Bacteria evolve and become resistant to antibiotics by natural selection. Antibiotics bind to specific parts in the ribosome and bacteria find ways to prevent the antibiotic to reach these pockets. Resistance can involve bacterial enzymes that degrade the antibiotic, or the bacteria can mutate the target molecule so that the antibiotic cannot bind to it anymore, or they use efflux pumps, which are proteins that pump out chemicals from the cell, including antibiotics. "No matter what antibiotic you develop, eventually there will be resistance," admits the professor. For example, scientists thought vancomycin would be unaffected by resistance, yet after just ten years, bacteria resistant to vancomycin emerged. "Never underestimate natural selection and evolution" concludes the professor.

What to do against antibiotics resistance?Although bacteria resistance is becoming a serious problem, the truth is that there are not many pharmaceutical companies interested in investing in new antibiotics. Developing a new drug costs about 1 billion dollars, but the new antibiotics would be given only to the patients who have resistant infections and are taken only for a short period of time. This is different from other drugs, like cholesterol drugs, which are taken for many years. Sir Ramakrishnan reminded that penicillin was funded by the British government, not by private companies. "It is a problem. We know there is going to be a rise in antimicrobial resistance and eventually more people are going to die of resistant infections in the future. Should we wait until we have a crisis in order to invest or should we go ahead and invest in it? This is an ethical and social question that governments need to ask," commented the professor. Professor Ramakrishnan's message for the next generation of scientistsProfessor Ramakrishnan is also President of the Royal Society, with whom IBS has been collaborating. Former fellows of the Royal Society like Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin left a big mark on the world. In the final session of the talk, Professor Ramakrishnan was joined onstage by KIM Gi Wook and MIN Kyeong Jin, two young chemistry students representing the student body of SNU. Students were curious to know the role of this British society that supports science: "The Royal Society is the oldest scientific body in the world; it was established in 1660 and, interestingly, set up by very young and engaging scientists," answered Professor Ramakrishnan. "They believed in rigorous fact checking and not blindly accepting an elder's opinion, everything had to be fact based, everything based on empirical evidence, hence the motto of the Royal Society 'On Nobody's Word'. I always stress the importance of teaching science properly from a young age and engage with the British public, informing them on our research, on CRISPR, on any global scientific issue that directly affects them. I am an advocate of science and we stress to the UK government that their scientific policy should be evidence based." He also urged public and scientists to get involved in science outreach of basic science, as the government funding in the field is based on taxpayers' money Prof. Ramakrishnan thinks that a Nobel is not the end result: "We still need to understand how the ribosome works, how it is regulated by the cell, how viruses can use the ribosome to build their own proteins. We must keep on going. […] My proudest achievement is not winning a Nobel, but seeing my research used in a text book for students. That fills me with more pride than the Nobel."

"We are excited to have Professor Ramakrishnan here in Korea and to hear about his big and courageous transitions, and major breakthroughs throughout his scientific career," comments KIM V. Narry, Director of the IBS Center for RNA research. Prof. Ramakrishnan changed career from physics to biology after his PhD and advised the young scientists not to be afraid of failure. "Science is not only about great discoveries. A great discovery is built on hundreds of other sort of incremental discoveries. I think you have to think of science as a collaborative enterprise, not just a few highlights. The first and most important attitude is to have a really genuine curiosity about your problems. From that, other things will flow," suggests the professor. IBS has already had two joint conferences with the Royal Society and plans to increase the level of collaboration, including exchanges of scientists between the UK and Korea. Letizia Diamante |

|||||

| Next | |

|---|---|

| before |

- Content Manager

- Public Relations Team : Suh, William Insang 042-878-8137

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20