주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

| Title | How to produce 1,000 scientists capable of competing for Nobel Prizes within 10 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Department of Communications | Registration Date | 2015-11-08 | Hits | 2948 |

| att. |

thumb.jpg

thumb.jpg

|

||||

|

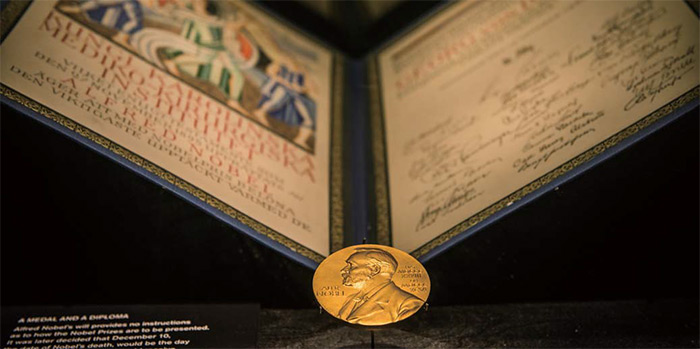

How to produce 1,000 scientists capable of competing for Nobel Prizes within 10 years ‘Basic Research Development Plan for a Creative Future’

To produce 1,000 world-class scientists capable of competing for Nobel Prizes by 2025 is one of the key objectives of the "Basic Research Development Plan for a Creative Future," which was reported at the 27th Presidential Advisory Council on Science & Technology presided over by President Geun-hye Park at the Blue House on October 22, 2015. Another objective of the Plan is to provide a foundation for sustainable growth by creating 10 world-leading technologies through basic research. Under the Plan, the government established specific policy measures for the innovation of its support system to enable leading basic research. The government’s Plan resulted in a mixed reception from researchers: although the intention to strengthen support for basic research was taken positively, the objective of producing, within just 10 years, 1,000 scientists capable of competing for Nobel Prizes received skeptical responses. A paradigm shift from being a “fast follower” to a “fast mover” Korea’s basic research began to be equipped with a support system through the passing of the Basic Research Promotion Act in 1989, and the scope of support has been expanded since then. For example, five-year comprehensive plans for the promotion of basic research have been implemented since 2005 and the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) was established in 2011, as a research organization that seeks excellence in basic science.

The lagging qualitative growth of basic research stems orom the fact that it is a relatively new field in Korea, with less investment and accumulation of knowledge than those of advanced countries. In addition, the government has been focusing on quantitative performance, including the number of papers and patents, by applying uniform evaluation metrics to basic research projects. Actions speak louder than words The government’s plan to strengthen basic research created expectations among researchers. However, they also expressed disappointment with the objectives of producing 1,000 world-class scientists who are capable of competing for Nobel Prizes and creating 10 world-leading technologies because there have been lots of hastily created projects to meet the government’s goals that were nothing more than slogans. Written by Geon-ho Kwon | Journalist for the Etnews |

|||||

| before | |

|---|---|

| before |

- Content Manager

- Public Relations Team : Suh, William Insang 042-878-8137

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20