| 공고명 | Investigating the Nose... Revealing the Secrets of the Immune Barrier | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 업무형태 | 입찰마감일 | ||||

| 담당처 | 전체관리자 | 등록일 | 2023-07-12 | 조회 | 155 |

| 첨부 | |||||

|

|

|||||

Investigating the Nose... Revealing the Secrets of the Immune Barrier

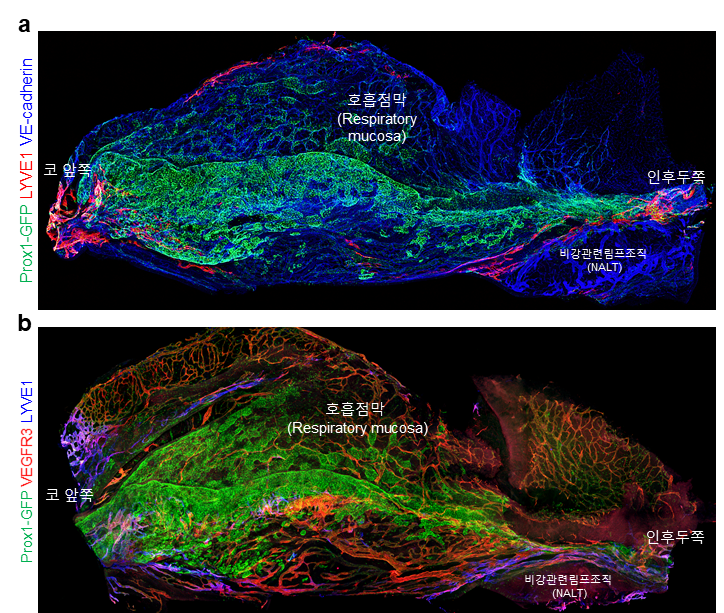

The nose is the first gateway encountered by external air entering the lungs. The air in the external environment is mixed with pathogens and foreign substances. The mucous membrane in the nasal cavity acts as the first line of defense by blocking these pathogens. However, how the nose acts as a defense barrier is not yet clear. This is due to the nose being not recognized as a relatively important organ, in addition to its complex structure with multiple layers of overlapping bones. There are scientists studying the nose, specifically analyzing the nasal blood vessels and lymphatic vessels in three dimensions. I met HONG Sun Pyo, a vascular scientist and a research fellow at IBS Center for Vascular Research. Q. Please introduce yourself.I graduated from Chungbuk National University with a degree in Biochemistry in 2013. After that, I pursued an integrated master's and doctoral program at the Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering (GSMSE) at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). During my doctoral program, I conducted research on cardiac cell and cardiovascular differentiation. My advisor during the doctoral program, Professor KOH Gou Young from KAIST GSMSE, moved to the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in 2015. Ever since then, I have been working as a researcher at the Center for Vascular Research. After obtaining my doctoral degree in 2018, I began working as a senior researcher at the IBS. At that time, I researched the role of lymphatic vessels in the villi of the small intestine and the mechanisms that maintain their roles. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, nasal blood vessels and lymphatic vessels have been the primary focus of my research. Q. Please introduce the IBS Center for Vascular Research as well.The IBS Center for Vascular Research is a research group that studies the structure and function of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels in different organs. Recently, we have been paying attention to the lymphatic vessels in the brain meninges and the cervical region. We are intensively studying the new functions and structures of lymphatic vessels in the brain meninges and cranial regions. If the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid is not properly facilitated through the lymphatic vessels, it can lead to diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer's. We are conducting basic research to find mechanisms that can help prevent various diseases. Currently, the research center is led by Director KOH Gou Young and consists of two research fellows, one postdoctoral researcher, ten students, and seven research and administrative staff members. Each individual is conducting research in various fields such as brain meninges, nasal cavities, and cancer cells. Q. What is your main research area?My research area is primarily the nose. The nose is the first organ in the body to be exposed to microorganisms in the air. In particular, the mucous membrane in the empty space of the nose, called the "nasal cavity," plays a role in blocking external pathogens and foreign substances. It serves as the initial immune barrier, and the blood vessels and lymphatic vessels in the nose are important for the immune barrier to function properly. The immune cells recognize the external pathogens and travel through the lymphatic vessels, then move to specific organs through the blood vessels. I am studying these blood vessels and lymphatic vessels structurally and molecularly. Q. What are your achievements?We have created a three-dimensional (3D) detailed map that allows us to examine the complex blood vessels and lymphatic vessels inside the nose. Prior to this, there had been no anatomical research conducted on the nose. There were only fragmented images of thin sections, and there had been little research on lymph nodes and vascular structures inside the nose. We also conducted a molecular analysis using single-cell analysis methods. This allowed us to elucidate the molecular and cellular characteristics of immune responses. Furthermore, we confirmed the wide distribution of "dural venous sinuses" within the nasal cavity, in addition to the typical capillaries. Dural venous sinuses are vessels through which venous blood circulates, and they were found to express adhesive proteins that can capture immune cells. This suggests that when external pathogens enter the nose, immune cells first migrate through the dural venous sinuses.

Q. I'm curious about the practical applications of the detailed map of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels inside the nose.Previously, we were limited to only viewing the nasal blood vessels, which made it difficult to understand all the interconnections in the vascular network within the nose. With the 3D map, we can visualize the entire vascular network. This enables us to accurately analyze the circulation process of blood and lymph fluid, determining where they enter and exit. Furthermore, blood vessels and lymphatic vessels have distinct heterogeneity in different organs. Using the created map, we conducted a molecular analysis of this heterogeneity, which would allow for a better understanding of the nose. With a higher level of understanding, we can discover methods to regulate drug delivery and better defense against pathogens. Additionally, we expect that this research will contribute to the study of effectively activating the immune response to future unknown infectious diseases that may emerge after COVID-19 Q. Were there any difficulties encountered during the research?The internal structure of the nose is highly complex, and elucidating its structure

has been a challenge in the academic field. We primarily conducted experiments

on mice, but imaging only the nasal mucosa from the small nose of mice proved

to be difficult. Isolating each small structure was extremely challenging. Q. How did you overcome these difficulties?Ultimately, it came down to the know-how. After numerous attempts, we succeeded in isolating the nasal mucosa of the mouse. We utilized existing imaging devices and techniques and went through several rounds of experimentation to study the mucosa. The fact that there were so few scientists who even attempted to study the nasal mucosa posed more challenges in our endeavor to examine the nasal cavity of mice. However, our research team ultimately succeeded. Q. What was the background behind starting your research?The background for starting this research was due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While scientists have had an interest in the nose for conditions such as allergies and rhinitis, there was no awareness of the importance of the nose in terms of respiratory infection in healthy individuals. However, the nose was identified as a primary route of infection in COVID-19. Our research team identified that ciliated epithelial cells in the nasal cavity were the primary targets for the initial infection and replication of the coronavirus. Q. What are the reactions in the academia regarding your research?The research findings have garnered significant interest from the scientific community and were shared on social media platforms like Twitter. This is mainly because the 3D visualization of the nasal structure was something that had never been done before, and the discovery of unique protein expression patterns in the nose was also a completely new finding. Additionally, there are pretty much no laboratories in the world that focus on nasal vasculature and lymph nodes. Due to our work being the first of its kind, there has been a great deal of attention and interest. We believe our work has opened an entirely new branch of research. As this is still a relatively unexplored field, it presents a promising future research area for scientists worldwide. Q. As the Center for Vascular Research revealed that the nose has an important role in disease infection, do you believe the use of nasal spray vaccine will be a gamechanger in dealing with future pandemics?Recent research suggests that administering vaccines through the nasal route can lead to the formation of a different type of immune response. During the COVID19 pandemic, studies were conducted in some countries involving intranasal administration of inactivated COVID-19 virus, which resulted in the formation of effective vaccination for a large population at a lower cost. If we can further analyze the differences between nasal vaccines compared to conventional vaccines and demonstrate that nasal vaccines can have superior efficacy, it is possible that these nasal vaccines could become a game-changer. Q. Has there been any interest from nasal vaccine development companies?During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been contacted by some vaccine development companies. Most of these contacts involved consultations, and now the development of nasal vaccines is in the early stages. The focus of the industry appears to be on preparing for new diseases rather than specifically targeting COVID-19. There are still challenges for nasal vaccines to demonstrate their efficacy, such as ensuring that the vaccine material can pass through the nasal epithelial cells and reach the tissues inside the nose. Q. We are curious about your future research plans.The lymphatic vessels play the role of "sewer system" for the body, by absorbing and processing waste materials. To serve this purpose, these vessels are loosely connected to allow waste materials to enter. However, the lymphatic vessels in the nose appear tightly connected. This tight connection is believed to prevent excessive immune reactions by limiting the movement of pathogens from the external environment into the lymph nodes. However, this is still a hypothesis, and further research is needed to understand the reason behind this feature. Additionally, we would like to study how pathogens can travel through the nose and infect the brain. Q. Are there any plans to make detailed blood and lymph vessels maps of other organs than the nose?We have a decent level of mapping for blood vessels in various organs. We plan to focus on expanding the mapping of lymphatic vessels. Currently, there is a lack of mapping that takes into account molecular heterogeneity for different organs. We are planning to conduct research on the heterogeneity and molecular mapping of lymphatic vessels in different organs Q. What kind of support do you think you will need for future research?I think IBS is the best research institution in Korea for conducting research. We receive excellent support in terms of research funding and equipment, so there are no difficulties in that aspect. However, it would be ideal if we can have an environment where good researchers can continue to work together. To ensure this, there needs to be a stable environment for talented researchers, as well as a continuous supply of students for them to work with. Resolving these aspects will enable good researchers to continue dedicating themselves to research. Q. Please give us some last comments.As a researcher, outputs are important. However, if we only prioritize outputs, we may end up chasing after papers and research that follow current trends. To conduct more in-depth research, it is necessary to maintain scientific curiosity. It is always challenging, but I believe we can continue to publish good results. I hope that all researchers who face these concerns can find solidarity. |

|||||